Should managers be technical?

December 18, 2022

Original posted on Proof of Concept

“Should managers be technically excellent in their craft? What a skill level should they maintain? This is a question I get a lot during office hours, mentorship sessions, and via email. In May, Elon Musk tweeted his perspective on this. The tweet stated:

“I strongly believe that all managers in a technical area must be technically excellent. Managers in software must write great software or it’s like being a cavalry captain who can’t ride a horse!”

Brian Chesky, Airbnb CEO reposted the tweet in agreement about design leaders being technical. Posts on Twitter usually prompt reactions over rational thinking. What often happens with tweets like this is a strong reaction in agreement by the fans or a very reactive dispute to it. I’ll extract the two tweets into the following discussion points:

- It’s important for leaders to be technically excellent

- Managers should be highly skilled in the discipline they lead (based on the calvary captain metaphor)

- Leaders should be spending time doing the work (Chesky’s comment)

This is essentially three elements: knowledge of your domain expertise, your responsibilities, and how much time you do it. Though my primary discipline, this concept applies to other functions such as engineering, product, or any other technical role.

The key roles of managers are to set expectations, ensure the team is operating efficiently, and maximize the output of the people on your team. In order to develop people, you must have a certain level of understanding of what skills are needed for people to be successful. However, as you progress in your career, there are going to be different org structures in place where it’s relevant. If you’re a Chief Product Officer, they likely have a more broad level of understanding of other functions outside of their domain and will put leaders in place who have the depth of knowledge in those areas.

Foundational skills

One of the missed opportunities in evaluating the skills of individual contributors and people managers is striking a strong divide between the skills. I cannot stand the term “soft skills” because they are foundational skills for both roles. As a design leader, there was likely a point you were the best designer on a team—with “best” and “a team” not “the team” are this statement’s keywords. You’ve risen to the ranks because of your impact and excellence as a contributor. Now, you encounter an inflection point if you want to focus more as a very senior individual contributor or move into management.

Regardless of the path you chose, this is where influencing through coaching and developing people is crucial. There is a certain level of comprehension needed in your domain. A piano instructor needs enough experience to teach various levels the same way an NBA coach should have played the sport at a high level. Do you really need Hans Zimmer to teach you how to play the piano or Michael Jordan with basketball? As cool as it would be, it’s not necessary. You also don’t want someone as your manager who just finished a boot camp or online course. Certainly, they have the potential to grow into this role, but you need more experience.

It’s about how you apply your skill to a role

Career development looks more like unlocking attributes for a different subclass in a role-playing game than picking a distinct class that can never change. It’s not a path. It’s a collection of skills and attributes focused on certain outcomes. Applying foundational skills is heavily contingent on your role and responsibility.

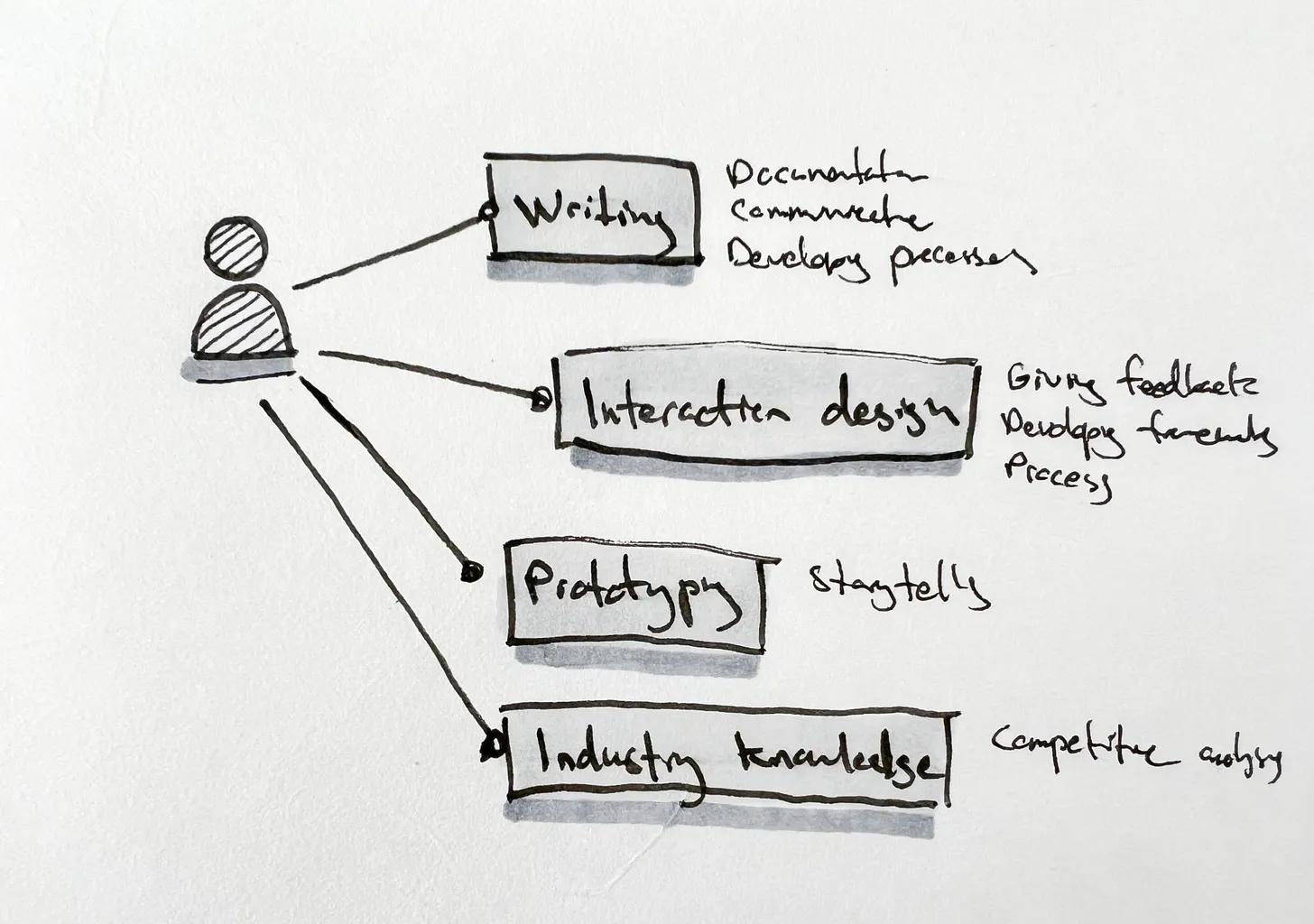

This sketch depicts how a manager might apply core skills to her day-to-day. In the end, it’s the same competencies applied in a different way. If a design systems team needed to get staffed, the individual contributor might apply skills by directly doing the work whereas the manager might use it to define a rubric on who to hire.

Time spent and scale of the team

I strongly do not agree with Chesky that design leaders should be spending most of their time designing and doing the actual work. It honestly sounds like he misses being a designer. That said, I think it’s important for leaders to invest time in exploring new innovations to learn/grow. Reviewing work is crucial to scale excellence, but allow your team to own the decisions.

There are many different types of management roles out there, and depending on what the company is, its scale, and other distinct attributes, the role and responsibility are going to look different. However, having deep technical skills allow you to scale teams longer term. Let’s say you’re an experienced Product leader. You’re taking on a new challenge at a startup as the first product manager with the intent to grow the team. When you’re the 0-to-1 leader you start by doing the work, establishing the foundation, and growing the practice as the company grows.

Recap

I want to end to articulate my point of view:

- Technical skills and acumen are important to articulate strategy and help develop people on your team

- The role of leading people is force-multiplying the output of people. When you’re doing the work yourself, it limits the time for you to be able to do that at scale

- Practice your craft in a way to be at the cutting edge of it to lead effectively and only do the actual work when it calls for it

The cavalry captain should be able to ride a horse but get them off the front lines as they should have more important stuff to work on! Management is something you take on when the value of your team is more important to develop others and help them drive towards shared outcomes that are more impactful than your own. Having more depth in the technical acumen of your field will only give you more range to help others grow. If I had to sum it up, you’d want your manager to be like that army general that still carries the World War II pistol around. He’s never going to use it, but you have the confidence if something came up that they have lived experiences to be able to roll their sleeves up and take action.

I'm David. I'm a designer, investor, and writer based in California.

I'm David. I'm a designer, investor, and writer based in California.