Jodorowskys Product Roadmap

I’ll share two stories you may not have heard of. These are stories of “the greatest film never made” and “the most important dead company in Silicon Valley.” This is a story about what happens when projects with uncompromising visions collide with the production process to make it happen (and keep it alive).

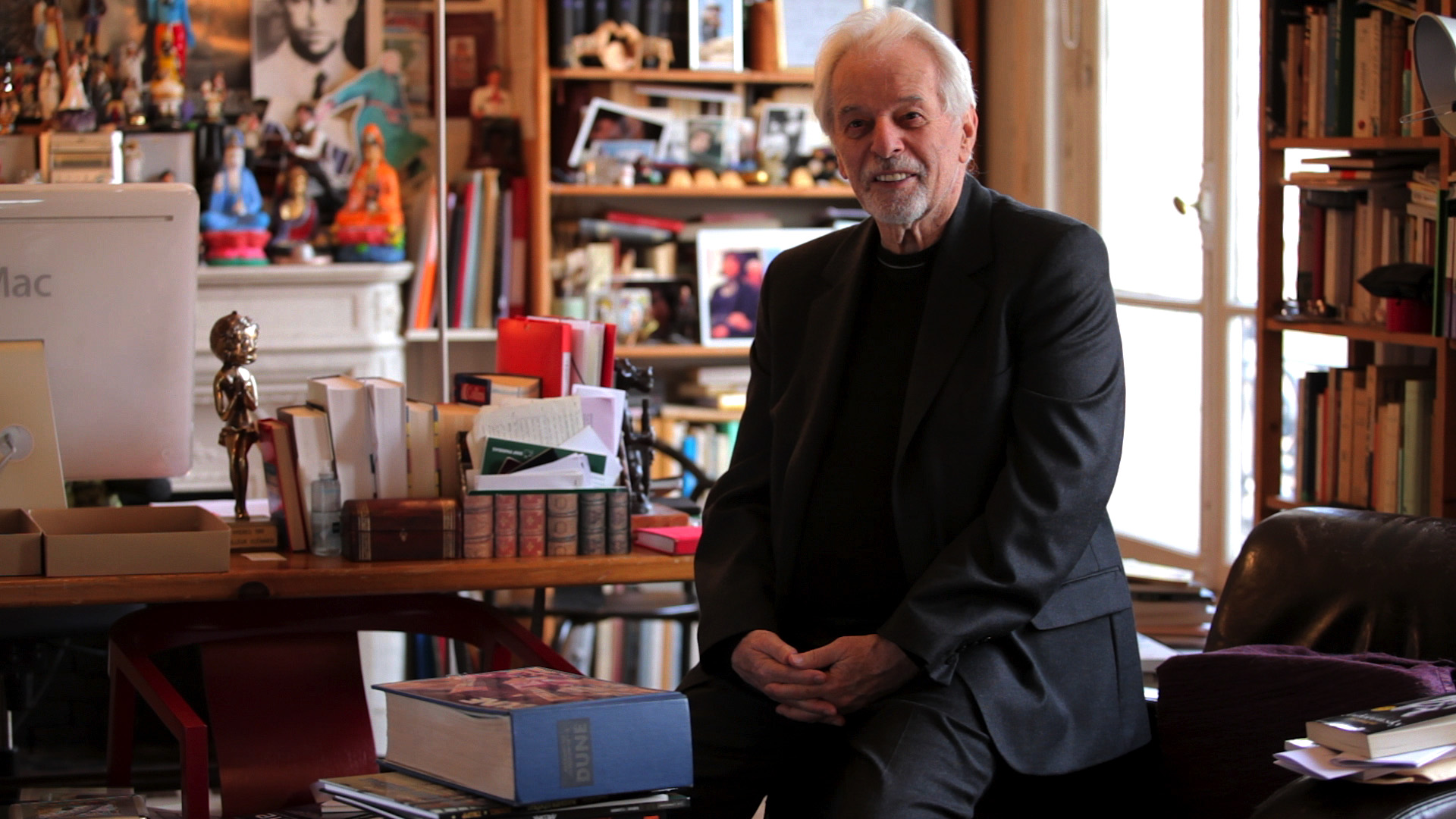

In the 1970s, film director Alejandro Jodorowsky took on what people said was the impossible task, a film adaptation of Dune. If you don’t know who Jodorowsky is, he is a filmmaker known for his avant garde and wild ideas. Dune is a science fiction novel written by Frank Herbert in 1965 and considered by some critics to be the best science fiction book ever written—the bible of science fiction. A film adaptation was often believed as impossible due to the epic length and many storylines of the novel.

From the beginning, Jodorowsky had a grand vision, and names such as Salvador Dali, Mick Jagger, Orson Welles, and Pink Floyd were set to star in the film. He even offered to pay Dali a fee of $100,000 per hour. Personally, I think that’s a pretty good rate in 1974. Jororowsky had an uncompromising vision, proclaiming that there would be no script notes, and the film had to be produced 100% aligned with how he imagined it.

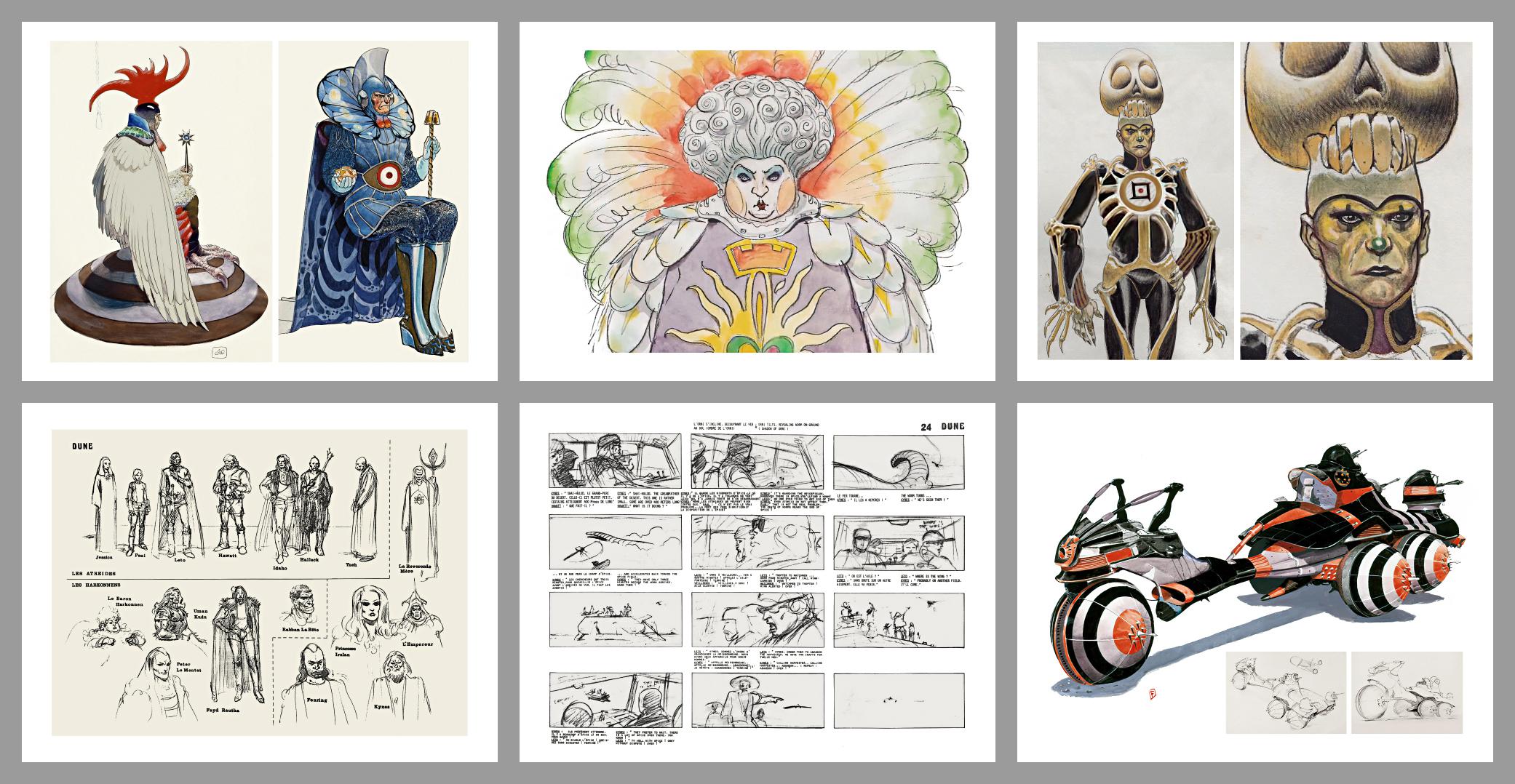

In addition to the star power of the on-screen talent, the designers who Jodorowsky recruited might be lesser known to the general public, but perhaps a larger impact. This design cast included Chris Foss (a well known science fiction cover artist), Jean Giraud (better known as Moebius in the comic book world), and H.R. Giger. Jodoroswky would lead his team of spiritual warriors who would make Dune come to life on the big screen.

The team of spiritual warriors spent $2 million of the $9.5 budget on pre-production with the film being about 14 hours long, and he wanted the film to be 20 hours. No rational production studio would take the risk on Jodoroswky’s massive vision, the hope of this film actually being produced collapsed. With the project dead, the rights were sold to producer Dino De Laurentiis in 1984 (yes, he’s the grandfather of Giada from The Food Network), who ultimately hired David Lynch to direct. All that was left in Jodorowsky’s Dune was a book of concepts and storyboards the size of a yellow pages phone book.

The dream was over.

Jodorowsky’s Dune is a prime example of an compromised vision that never made it to reality, and there are many other industries that have similar stories, such as technology and startups. Let’s take a look at another story in Silicon Valley. You have not heard of General Magic, but you are likely familiar with the iPod, iPhone, and Android phones.

The year was 1989 and Apple Inc. headed by John Scully, the former Pepsi CEO who co-founder Steve Jobs hired, and ultimately was fired by. Without Jobs at the helm, the computer company was looking for new product innovation. Apple employee Marc Porat, known for his entrepreneurial spirit and big ideas, convinced Scully that the future of computing would be a partnership of computer, communications and consumer electronics companies. Known as the Paradigm project, the initiative lacked traction internally at Apple. Porat took the initiative and spun it out as its own company separate from Apple. General Magic was born. Porat recruited two key Apple engineers, Andy Hertzfeld and Bill Atkinson to join this ragtag team of magicians to build the future of computing.

General Magic’s worked on an operating system called Magic Cap designed with mobile computing in mind, which was a wild idea in the early 90s when you still had to call the internet to connect. Magic Cap used the metaphor of rooms as a virtual office you could navigate on your mobile device. General Magic was able to get further in production than Jodorowsky simply by existing and still having money to work on their vision.

As the General Magic team continued to innovate in the future, Apple would release a portable digital assistant called the Apple Newton. This was done with Scully still as CEO of Apple and without General Magic’s knowledge. The product was a flop. From a vision and execution perspective, if General Magic was Jodorowsky’s Dune, then the Apple Newton was David Lynch’s Dune.

General Magic was able to get further than Jodorowsky’s Dune in terms of tangible results, but they also struggled with compromising on their vision. Somehow, the company was able to IPO in 1995 without an actual product, likely with investors making a bet on the team’s vision that still hasn’t been productionalized. Four years after their IPO and finally a product rushed to market without major adoption by consumers.

The dream was over.

The greatest film never made and Silicon Valley’s most important dead startup never achieved their visions. Or did they? How is success defined? Is there such a thing as being too ahead of your time, or the vision being too big? Without such big dreams, would we continue to build a faster horse?

Should these two visions have compromised in order to survive? In hindsight, some may argue they should have, but would it have been the same impact?

What remained in the concept art from Jodorowsky’s Dune lived on in a way the film director unlikely hoped for. George Lucas would create a little known film called Star Wars in 1977. In one of the most iconic opening scenes in film history, it was very reminiscent of Dune’s storyboards for the opening. H.R. Giger, one of Jodorowsky’s artists on Dune went on to work with Ridley Scott in the Sci-Fi horror film Alien. Giger brought his work style into the film that let the world know that in space, no one can hear you scream. Ridley Scott also was approached by Dino DeLaurentiis about directing Dune (The David Lynch one). Due to a personal tragedy, Scott dropped out and upon returning instead directed a film called Blade Runner, who borrowed work from Moebius for the art direction.

The list of former General Magic employees reads like a hall of fame of tech giants. Tony Fadell went on to invent the iPod, co-invent the iPhone, and start Nest. Megan Smith went on to be a VP at Google. Kevin Lynch went on to create a design/code editing software called Dreamweaver and went on to be a lead engineer on Apple Watch. He’s also the Apple exec often mistaken to be Bill Gates due to their resemblance. Andy Hertzfeld invented Google Circles which led to Google+ (he did useful things too!). Andy Rubin went on to invent the Android operating system later acquired by Google. He also is a really terrible human being so we’ll stop there. Even the low level employees found success after General Magic. Pierre Omidyar left the scrappy startup to start his own company, which he called eBay.

46 years after Jodorowsky first put together his phonebook-sized vision book, acclaimed director Denis Villeneuve will take on the ambitious project of Dune. With films like Prisoners, Siccario, Arrival, and Blade Runner 2049 on his resume, there is no doubt that the work of Jodoroswky’s concept book inspired Villeneuve.

Tony Faddell was just a college grad when he worked at General Magic and endured a decade of trials and tribulations working at the struggling startup. As Faddell once said in an interview, “I literally had a decade of failure.” Faddell would later go on to invent the iPod, be co-creator of the iPhone, and the Nest thermostat. It is quite possible the greatest value General Magic shipped was Tony himself.

As someone who works in startups and tech, there are multiple definitions of success and failure. For an investor, success might be scaling to a lucrative IPO for huge returns. For a founder, it might also be that, however, it could also be pursuing an uncompromising vision to change the world. The majority of startups die before their vision is even realized and never make it to market. However, some uncompromising visions often explore like a supernova spreading its cosmic influence for those to continue the work.

Perhaps the greatest failures at fulfilling a grand vision bore spores of inspiration for others to continue the work for countless generations.